It’s Tick Season—Know Your Enemy

This post first appeared in Forbes last year. While we are thinking of fall and that we can relax our guard, this is your friendly reminder that ticks are still quite active–and will be any time there is not a freeze.

It’s time to worry and ramp up your protective moves; tick season is getting more active. I can’t say it is just starting, as we found ticks on us and the dog in both January and February, most unexpectedly when we had unseasonably warm days. Any time it is above freezing is a risk, but April–September is prime time for the buggers. There are many different types of ticks, but the one we need to be most careful to avoid is the black-legged or deer tick, Ixodes scapularis (or Ixodes pacificus on the West Coast) because it transmits Lyme disease, often difficult to diagnose and treat, and a number of other infections.

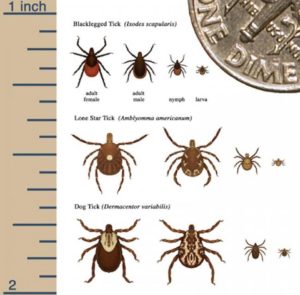

Deer ticks are most commonly confused with dog ticks, according to Dr. Tom Mather, director of the University of Rhode Island’s Center for Vector-Borne Disease and its TickEncounter Resource Center. Deer ticks and dog ticks are two of the three species most frequently submitted to TickEncounter. The distinction is important, as dog ticks, Dermacentor variabilis, are much less risky, and their bites do not transmit Lyme. Here are some clues to help you tell the ticks apart.

For more illustrations comparing the ticks, see TickEncounters.org. I urge readers to send a digital photo of their tick to TickEncounters, which provides a valuable free service. While they use this information for epidemiologic study, they will also rapidly respond with an identification of your assailant and an estimate as to how long the tick was likely feeding on you—important for deciding whether you need to take antibiotics.

Deer ticks, or black-legged ticks, Ixodes, are tiny, only about the size of a poppy seed or the period at the end of this sentence, when in the early larval stage. As they begin to feed and engorge, they become the size of a sesame seed, then a bit larger. The females have a prominent red back half and sides. These ticks prefer shaded, leafy areas like forest, though are found wherever there are deer and white-footed mice. Up to 50 percent of deer ticks in the Northeast carry the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme. An estimated 300,000 people get Lyme each year in the U.S., most in the Northeast or upper Midwest.

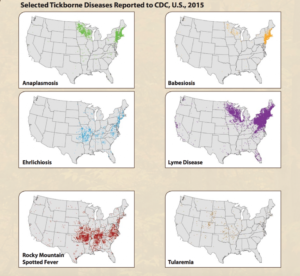

Dog ticks, Dermacentor, are mostly found in open grassy or shrubby areas and are much larger. These ticks, being larger, are easier to find on you or your pet. They have notable white markings on their back. The dog ticks can transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever on occasion or, rarely, tularemia (aka rabbit fever). While there has been an uptick in cases over the past decade, “spotted” fevers affect fewer, with over 60% of all cases occurring in North Carolina, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Missouri, though North Dakota, Kentucky, Mississippi, Kansas, Alabama, South Carolina, Delaware, and Virginia also have increased risk.

The lone star tick has been coming increasingly to attention as it spreads and as new diseases are associated with it. The females have a prominent white dot on their backs. These ticks are widely distributed throughout the Southeast and Eastern US, as well as the lower Midwest states. Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI) causes a rash similar to that of Lyme, but is not caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria which causes Lyme. In fact, scientists haven’t identified the culprit. It hasn’t been shown to cause the more serious types of illnesses Lyme does, such as arthritis or neurologic symptoms. Like Lyme and rickettsial diseases (spotted fevers), STARI responds to doxycycline.

The lone star tick also transmits ehrlichiosis, Heartland virus, and tularemia.

Soft ticks (Ornithodoros) transmit the tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) type of infection. They are found in rodent-infested cabins (not grasses) and often bite at night. Symptoms include fever, headache, and joint or muscle pain occurring in a relapsing, cyclical pattern.

What ticks transmit what diseases?

What to worry about depends on where you live or have been traveling and what kind of outdoor activities you indulge in. It is critical that you tell your physician about your hobbies and possible exposures, or a diagnosis for a rash or unusual symptoms might well be missed, especially since many of these infections are uncommon and most clinicians will never have seen one.

If you are in the Northeast, you are at particularly high risk of Lyme, anaplasmosis, ehrlichia, and Babesia, a parasite. The risk in the upper Midwest is similar, though less so, especially for ehrlichia. The Rockies are your safest bet for not getting a tick-borne infection, though they likely have their own problems.

Coinfections are much more controversial. On the one hand, the LymeDisease.org folks have done surveys in three thousand–plus people with “chronic Lyme” complaints (though that is an ill-defined entity) that indicate that coinfections are common. They claim 32% of patients with “chronic Lyme” are coinfected with Babesia, 28% with Bartonella, and 15% with erlichiosis, for example.

There are problems with this approach. Even if the diagnostic tests used are accurate—and many aren’t—there is no good data that shows that these are either related to tick bites or are the source of symptoms. For example, babesiosis may be a serious, acute illness with fever, anemia, and enlarged liver and spleen, especially in immunosuppressed patients. It is usually diagnosed by PCR (polymerase chain reaction) or by looking at a smear of a patient’s blood under the microscope and identifying the parasite in red blood cells, just as with malaria. Other people have had asymptomatic infections and have antibodies to their old infections. That doesn’t mean that the parasite is causing their nonspecific symptoms now.

Bartonella is generally transmitted by cat scratches, fleas, and lice (trench fever or Bartonella quintana in homeless people). Evidence for transmission by ticks is circumstantial, at best. The presence of Bartonella DNA (by PCR) does not mean that the tick transmitted an infection to a person. It may just reflect that the tick fed on an animal carrying the parasite from a previous meal.

This is an overview of the threats of infection transmitted by ticks. We are gradually discovering new illnesses, but with the dismal state of diagnostics, we have a long way to go.